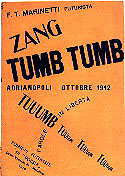

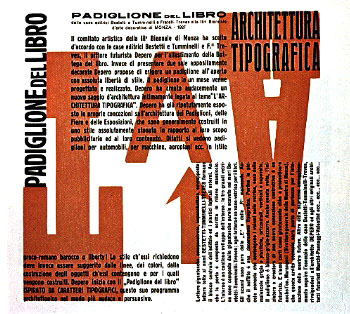

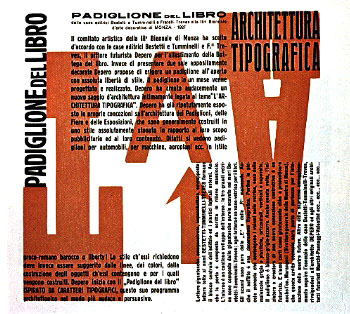

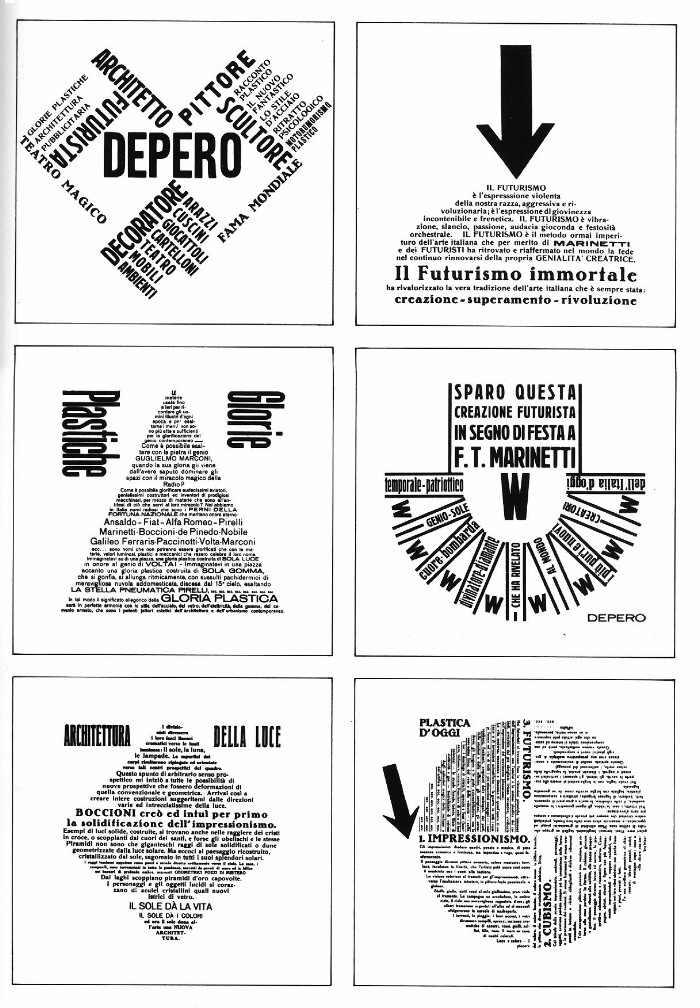

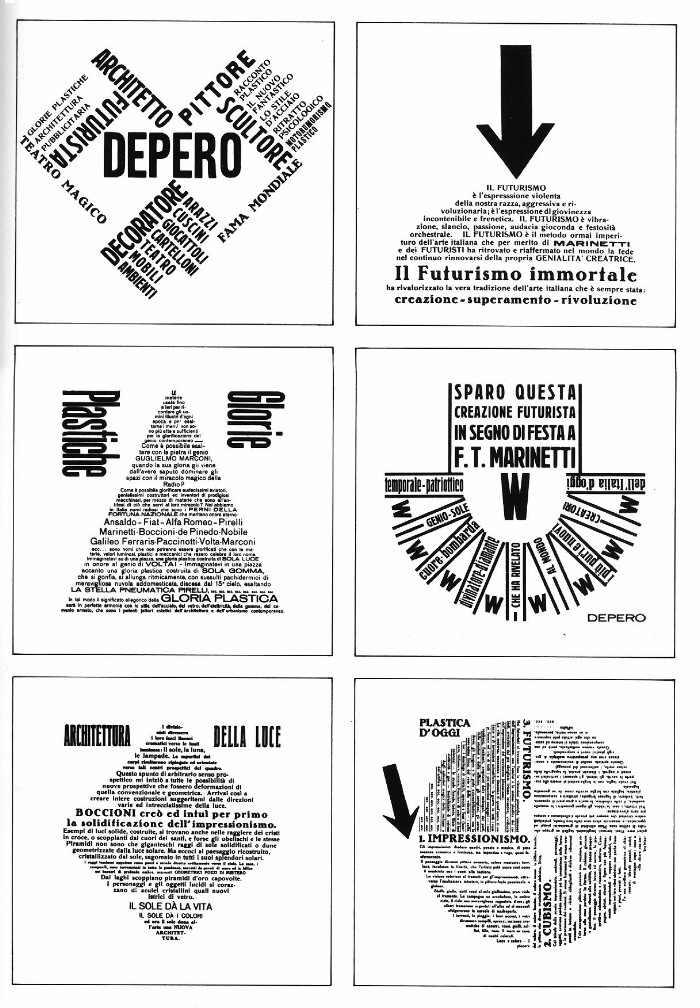

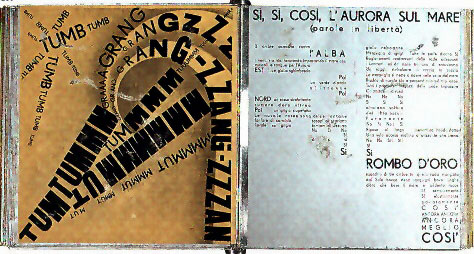

| Futurism (1909-1944) was perhaps the first movement in the history of art to be engineered and managed like a business. Since its beginning, Futurism was very close to the world of advertising and, like a business, promoted its product to a wide audience. For this reason, Futurism introduced the use of the manifesto as a public means to advertise its artistic philosophy, and also as a polemic weapon against the academic and conservative world. The poet F.T. Marinetti, founder of the movement, wrote in his first manifesto of February 1909,"Up to now, literature has exalted a pensive immobility, ecstasy, and sleep. We intend to exalt aggressive action, a feverish insomnia, the racer's stride, the mortal leap, the punch and the slap. We affirm that the world's magnificence has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. . . We will destroy the museums, libraries, academies of every kind, will fight moralism, feminism, every opportunistic or utilitarian cowardice."Futurism, as opposed to Cubism, an essentially visual movement, found its roots in poetry and in a whole renovation of language, and featured the concept of the New Typography. Since 1905, Marinetti had promoted from the pages of his magazine Poesia (Poetry) the idea of verso libero(free-verse), which was intended to break the uniformity of syntax of the literature of the past. Then, just after the launch of the Futurist movement, verso libero evolved into the parole in libertà (words-in-freedom), the purpose and methodology of which were outlined in a manifesto dated 1913 and bearing the long title Destruction of Syntax/Imagination without Strings/Words-in-Freedom. In this manifesto Marinetti stated: "Futurism is grounded in the complete renewal of human sensibility that has generated our pictorial dynamism, our antigraceful music in its free, irregular rhythms, our noise-art and our words-in-freedom . . . . By the imagination without strings I mean the absolute freedom of images or analogies, expressed with unhampered words and with no connecting strings of syntax and with no punctuation."These last lines of the quotation were already included in a previous manifesto of May 1912,Technical Manifesto of Futurist Literature, where Marinetti proposed that writers "banish punctuation, as well as adjectives, adverbs, and conjunctions." Actually, an elimination of punctuation had already been practiced by Mallarmé in his poems "Un coup des Dés jamais n'abolira le Hasard," published in Paris in 1897 in the magazine Cosmopolis. However, this magazine had very little impact, even within literary circles. It was published as a book only in 1914, and until that year it was almost unknown. Marinetti's theories, on the other hand, thanks to the wide circulation of his manifestos, were widely circulated since 1912 and influenced the work of hundreds of writers and poets throughout Europe, including Guillaume Apollinare (in his early calligrammes, like Lettre-Ocean), Blaise Cendrars, Reverdy, etc. In The Destruction of Syntax manifesto, Marinetti wrote: "I initiate a typographical revolution aimed at the bestial, nauseating idea of the book of passéist and D'Annunzian verse, on seventeenth Century handmade paper bordered with helmets, Minervas, Apollos, elaborate red initials, vegetables, mythological missal ribbons, epigraphs, and roman numerals. The book must be the Futurist expression of our Futurist thought. My revolution is aimed at the so-called typographical harmony of the page, which is contrary to the flux and reflux, the leaps and bursts of style that run through the page. On the same page, therefore, we will use three or four colors of ink, or even twenty different typefaces if necessary. For example: italics for a series of similar or swift sensations, boldface for violent onomatopoeias, and so on. With this typographical revolution and this multicolored variety in the letters I mean to redouble the expressive force of words."Marinetti's theory of "words-in-freedom" was central for the renewal of typography in this century, and his book Zang Tumb Tumb (1914), with its explosive layout, is undoubtedly a masterpiece in this field. Even El Lissitzky, in his writings on new typography, quoted Marinetti's theories as a starting point for everyone involved in experimental and modernist book-making. For the Futurists, book-making was in fact the result of a precise theory to adhere to when conceiving their books. Futurist books led to the future (hence the name of the movement), functioning as emblems of technical and cultural progress, and using all possible media of serial production in the mechanic age. Thus, mass production and distribution was vital to the spread of their works, as well as to the Futurist philosophy itself. "We stand," proclaimed Marinetti, "on the last promontory of the centuries! Why should we look back to the past?" During the same years Italian Futurism was flourishing, the Russian Futurists were also devoted to a wide experimental movement in book-making that was inspired by a very different ideology. The Russians' philosophy considered books to be works of art, and often featured original illustrations or unique, hand-made covers, and were printed in very limited editions. This approach was not the result of a specific philosophy of typography (as was Marinetti's) but rather the consequence of the philosophy from which the Russian avant-garde was born. This ideology was characterized by the revival of Russian cultural heritage (for example, the re-evaluation of the lubok (devotional folk painting) as a mystical image linking them to their roots), and a state of closure toward the West, which was seen as potentially threatening to their old traditions. Marinetti's theories were widely influential and resulted in the production of hundreds of books by many Futurists. The books were often characterized by nearly anonymous covers with explosive inner pages where often traditional typefaces were eschewed in favor of newly designed typefaces that spread over the pages without any respect to the rules of layout. These new "alphabets" were designed in order to express different stati d'animo(states of mind), and often were put together to form various and odd shapes; suddenly, word became image. A perfect example of this movement is Francesco Cangiullo's book Caffè-Concerto - Alfabeto a sorpresa (Café-Chantant - Surprising Alphabet), completed in 1916, but printed after the war in 1919). Cangiullo uses words in different typefaces to form images of scenery, landscapes, and even human bodies. During the 1910s, Futurist book-making was devoted mainly to such typographic experiments in "words-in-freedom" which were finally summarized in the book Les mots en liberté futuristes (The Futurist Words-In-Freedom) by Marinetti in 1919. In the 1920s, Futurism's new direction of emphasizing the "mechanic age" gave new energy to the movement. The masterpiece of this decade is surely the famous bolted book, created by Fortunato Depero in 1927. But if the binding itself was a real mechanic manifesto, the layout was a revolution in book-making. The multicolored text is printed on different kinds of paper, in typefaces of varying shapes and sizes that give life to vibrant geometric shapes. The book has neither up nor down, right nor left; not one but many virtual layouts, so that in order to read the text, the book has to be turned round and round again.Finally, in the early 1930s, Marinetti published another famous book, Parole in Libertà Futuriste, olfattive, tattili, termiche (The Words-in-freedom, Futurist, Olfactive, Tactilist, Thermal) that was printed by a lithographic process in many colors on metal sheets, and with a metal binding. With this metal book (followed in 1934 by another one with illustrations by Bruno Munari, L'anguria lirica(Lyric Cucumber), the Futurist experiments on bookmaking reached their highest point and ideally closed the circle of over 25 years of literary, poetic and typographic innovations. Return to Colophon Page Table of Contents |

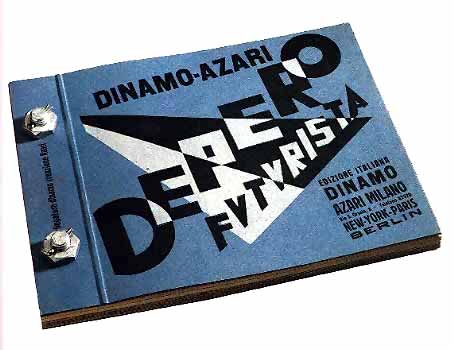

Fortunato Depero, Depero futurista 1913-1927 (Depero the Futurist 1913-1927), 1927.

Book bound with two bolts.

Book bound with two bolts.

This book is a first-hand account of the Futurist Fortunato Depero's (1892-1960) approach to Futurism until 1927. It featured for the first time a mechanical binding consisting of two bolts holding the pages together, as conceived by Fedele Azari, the publisher. Influenced by the focus on the machine that characterized Futurism in the early 1920s, this book should be considered a manifesto of the Machine Age. However, Depero's innovation was not confined to the cover; the inside text features a wealth of typographic inventions including the use of different typefaces, the text formed into various shapes, the use of different papers and colours, and several other devices.

After seeing this book, Kurt Schwitters wanted to meet Depero and enthusiastically showed his copy to every visitor to his personal library. This book was published in an edition of 1000 copies, most of which bear a stamp of the number of the copy. The edition, showed at least three different front pages with different color prints. There are four or five copies with a metal binding -- books of great rarity but of minor visual impact. Finally, there were even four to five copies provided with a box case expressly designed by the author. This book is surely the first object-book in the history of printing, a work-of-art in itself, and also as a masterpiece of avant-garde book-making.

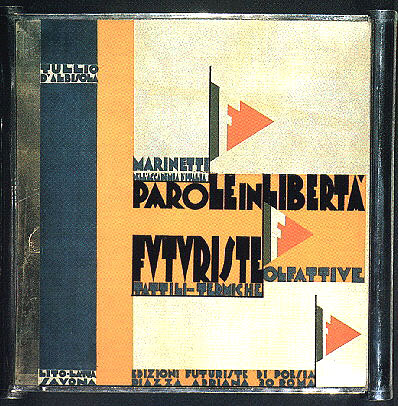

F.T. Marinetti, Parole in libertà: olfattive, tattili, termiche (Words-in-freedom: olfactory, tactile, thermal), 1932.

Cover by the author.

Cover by the author.

Just five years after Depero's sensational "mechanical" book that featured a two bolt binding, Marinetti introduced his definitive model of the mechanical book. While Depero's was printed on conventional material (paper), Marinetti's new book was entirely printed on metal sheets. In this way, the book came even closer to the signs of the Machine Age, and aimed to be an imperishable book. The book's content was no less interesting, as Marinetti introduced new references between words and physical interaction with olfactory, tactile, and thermal sensations.

Tullio d'Albisola, L'anguria lirica (Lyric cucumber), 1934.

Printed and bound on metal sheets, cover and illustrations by Bruno Munari.

Printed and bound on metal sheets, cover and illustrations by Bruno Munari.

This is the second, and actually the last, book printed on metal sheets by the Futurists. The author himself (Tullio d'Albisola) was also the publisher under the name of "Litolatta," a firm especially founded to produce such metal-books. Unlike the other famous metal book (by F.T. Marinetti), this one features illustration by Bruno Munari, now a world-renowned designer but at the time only a young, though talented, Futurist painter. While illustrations for Marinetti's book were essentially a kind of "visual poetry," Munari's are in a pictorial style, and, in particular, feature a cosmic allure typical of the time. Futurist painting followed the new theories of Aeropittura (Flight Painting) as well as reflected the influence of Enrico Prampolini, at the time the undisputed leading personality of the Futurist movement.

SOURCE:http://colophon.com/gallery/futurism/index.html