Sarah Boseley, health editor

The Guardian, Thursday 2 February 2012

Article history

Malaria is caused by Plasmodium parasites which are spread by female Anopheles mosquitos. Photograph: PA

Malaria kills twice as many people every year as formerly believed, taking 1.2 million lives and causing the deaths not only of babies but also older children and adults, according to research that overturns decades of assumptions about one of the world's most lethal diseases.

The findings from the research, published on Friday, which has reanalysed 30 years of data on the disease using new techniques, will force a rethink of the huge global effort that has been under way to eliminate malaria. That ambition now looks highly unlikely by the UN target date of 2015.

It also raises urgent questions about the future of the troubled Global Fund to Fight Aids, TB and Malaria, which has provided the money for most of the tools to combat the disease in Africa, such as insecticide-impregnated bed nets and new drugs. The fund is in financial crisis and has had to cancel its next grant-making round.

The research comes from the highly respected Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), based in Seattle, and is published in the Lancet medical journal.

Dr Christopher Murray and colleagues have systematically collected data on deaths from all over the world over a 30-year period, from 1980 to 2010, using new methodologies and inventive ways of measuring mortality in countries where deaths are not conventionally recorded. The work on malaria is part of a much bigger project which has already led to new estimates of the death rates of women in childbirth and pregnancy and from breast and cervical cancer.

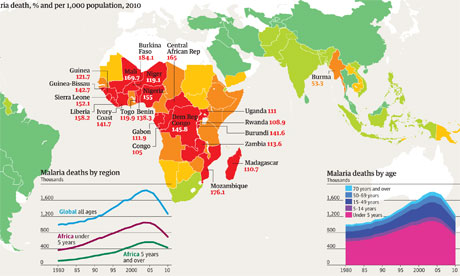

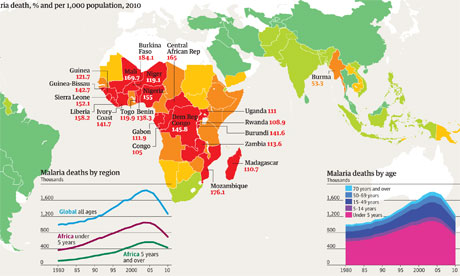

Click image to see the data behind this story

Click image to see the data behind this storyTheir figure of 1.2 million deaths for 2010 is nearly double the 655,000 estimated in last year's World Malaria Report.

The good news is that they have confirmed the downward trend that the World Health Organisation's report showed, as a result of efforts by donors, aid organisations and governments to tackle the disease.

The bad news is that the decline comes from a much higher peak – deaths hit 1.8 million in 2004, they say. That means the interventions such as better treatment and bed nets are working, but there is much further to go than everybody had assumed.

The study demolishes conventional thinking on malaria – that almost all the deaths are in babies and small children under the age of five. The study found that 42% were in older children and adults.

"You learn in medical school that people exposed to malaria as children develop immunity and rarely die from malaria as adults," said Murray, IHME director and the study's lead author. "What we have found in hospital records, death records, surveys and other sources shows that just is not the case."

Most deaths are still in children, but a fifth are among those aged 15 to 49, 9% are among 50- to 69-year-olds and 6% are in people over 70, so a third of all deaths are in adults. In countries outside sub-Saharan Africa, more than 40% of deaths were in adults.

In Africa, though, the contribution of malaria to children's deaths is higher than had been thought, causing 24% of their deaths in 2008 and not 16% as found by a report by Black and colleagues, whose methodology was used in the World Malaria Report.

That means that malaria needs a higher priority if the millennium development goal of cutting child mortality by two-thirds between 1990 and 2015 is to be achieved, say the authors.

They add: "That malaria is a previously unrecognised driver of adult mortality also means that the benefits and cost-effectiveness of malaria control, elimination and eradication are likely to have been underestimated."

There is a need, they say, to pay attention to the risks malaria poses to adults and they support the recent strategy to hand out insecticide-impregnated bed nets to protect all members of the household against mosquitoes carrying malaria parasites, instead of insisting they are only for babies and pregnant women, as was originally the case.

Malaria deaths have come down by 32% from 1.8 million in 2004 to 1.2 million in 2010 because of the sustained effort to get bed nets into homes, indoor spraying and new artemisinin combination drugs – older anti-malarials do not work in many areas because the parasite has developed resistance to them.

More than two-thirds of this has been paid for by the Geneva-based global fund, which has suffered from donors' unwillingness to invest more money.

"The announcement by the global fund that round 11 of funding would be cancelled raises enormous doubts as to whether the gains in malaria mortality reduction can be built on or even sustained," say the authors.

"From 2003 to 2008, the global fund provided 40% of development assistance for health targeted towards malaria. This reduction in resources for malaria control is a real and imminent threat to population health in endemic countries."

Professor Rifat Atun, director of strategy, performance and evaluation at the fund, said more than $2.5bn (£1.6bn) had been disbursed for malaria control between 2009 and 2011. By the end of 2011, 235m bed nets had been distributed. Money that had been pledged was still coming in, he said, which meant it would be able to invest substantially this year and next. "What we are not able to achieve is the rate of increase in investment of the last few years. The trajectory we have been able to establish will not be realised," he said. "Given the new burden that Christopher Murray has been able to show, we really need to ramp up investments in malaria and that really needs more funding. The mortality figures are much, much larger. We need to double our efforts to address the burden that we have." The Department for International Development said: "We are committed to helping halve malaria deaths in at least 10 of the worst affected countries. We will do this by increasing the number of bednets used by women and children; improving the diagnosis and treatment of malarial; and strengthening health information systems to better monitor progress and target interventions."

SOURCE:http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2012/feb/03/malaria-deaths-research

Malaria deaths country by country: how many are there?

What we thought we knew about Malaria deaths is wrong: the reality is much, much worse. See what the new detailed data says

• Get the data

Malaria cases have always been underestimated. This shows a truer picture. Click image to see graphic

Malaria causes twice as many deaths as previously believed, according to the latest research out today from the highly respected Institute forHealth Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), based in Seattle, and published in the Lancet medical journal.

That figure of 1.2 million deaths for 2010 is nearly double the 655,000 estimated in last year's WHO World Malaria Report, which we detailed on the Datablog here.

How were the figures so wrong? The assumption has always been that the majority of those who die from malaria are children. In fact, the deaths are much evenly spread than that - adults die too.

It also raises urgent questions about the future of the troubled Global Fund to Fight Aids, TB and Malaria, which has provided the money for most of the tools to combat the disease in Africa, such as insecticide-impregnated bed nets and new drugs. The fund is in financial crisis and has had to cancel its next grant-making round.

There is some good news in the data. Since the peak of 2004 of 1.8 million deaths worldwide, the number has fallen annually and between 2007 and 2010, the decline in deaths has been more than 7% each year.

Photograph: PA

Photograph: PAThe researchers said the key to collecting the new data was the use of verbal autopsy data.

In a verbal autopsy, researchers interview the relatives of someone who has recently died to identify the cause of death. IHME and collaborators around the world published a series of articles in a special edition of Population Health Metrics in August 2011 focused on advancing the science of verbal autopsy. Verbal autopsy data were especially important in India, where malaria deaths have been vastly undercounted in both children and adults. IHME found that more than 37,000 people over the age of 15 in India died from malaria in 2010, and the chances of someone dying from malaria in India have fallen rapidly since 1980.

We've extracted the data for deaths and death rates for all ages below. What can you do with it?

Data summary

Malaria deaths by country, all ages

Click heading to sort table. Download this data

Data summary

Download the data

Download the data

No comments:

Post a Comment